One of the overnight excursions I made last month on Lewis was to pay a visit to Beinnn a' Bhoth - the mountain of the beehive cell. Although it is only 1000 feet high, it is a challenge to climb as it it lies five miles south of the road at Kinlochrog. Five miles of ups and downs over boggy terrain.

So why, you ask, did I want to climb this remote hill? It was because of a cryptic note in Donald MacDonald’s Tales and Traditions of the Lews; a book posthumously published by his wife in 1967, six years after his death in 1961. (A paperback version was published by Birlinn in 2000.) The book includes a short chapter entitled The Beehive Huts on the Uig and Harris Hills, which ends with the following sentence: On the side of Ascleit are a group of boths (beehive cells) still with the roofs on and one on Beinn a’ Bhoth.

|

| Beehive cell on Ascleit (2018) |

I had easily found the Ascliet cells on a walk in 2018 (see the

September 7, 2017 post). But the cell MacDonald mentioned on Beinn a’ Bhoth was a complete mystery. Beinn a’ Bhoth (the mountain of the beehive) is 1000 feet high, and spans over two-square miles. The CANMORE database does not show any sites on the hill. Neither does the 1854 OS map, which is usually a good source to find ruins.

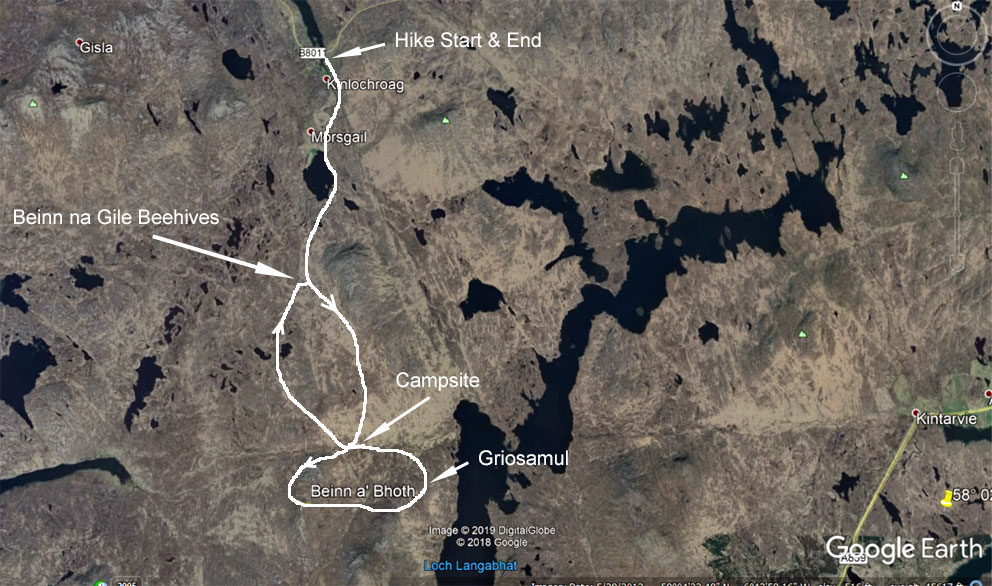

I knew I would not have the energy to walk over every square foot of the hill, especially after the long trek in, so I spent some time looking at the aerial photography overlays available on CANMORE. In scanning the images I noticed what looked like a small pimple high on the hill—possibly a beehive cell. During the walk described in the above referenced post I had passed right below it. In addition, I also noticed what appeared to be an intact cell at Griosamul, a mile east of the hill. And so a return to Beinn a’ Bhoth became a must. It would require a round-trip walk of 12 miles from Kinlochrog. A bit far for a day-trip, so I decided to make it an overnighter.

I was on familiar territory as I headed south along the track to Morsgail Lodge, crossed the footbridge just before the lodge, and then traversed down the eastern shore of Loch Morsgail. At the Beinn na Gile beehives I turned southeast to follow a very old track up to the saddle between the summits of Shèlibridh and Cleit Shèlibridh. From the top I had a clear view south to Beinn a' Bhoth.

|

| Beinn a' Bhoth (at centre) seen from Shelibridh |

From

Shèlibridh an easy descent south took me to the shielings of Airigh an-t-Sluic. This was where I would camp for the night in a few hours. To lighten my load for the rest of the day’s hiking I dropped my tent and sleeping bag next to one of the ruined shielings. Looming above me was Beinn a’ Bhoth, the mountain of the beehive.

The north and west sides of Beinn a’ Bhoth are a mix of steep, grassy slopes and craggy cliffs. I entered the grid coordinates into my GPS of the object on the aerial photo, and let the GPS guide me to it. As I climbed a grand view west to Loch Reasort and the Atlantic gradually opened up. When the GPS indicated I had 100 feet to go, I saw something, and gasped. Lying half enveloped in heather, moss and grass, stood a very old beehive. (Sorry, but I am not going to include a photo. I am saving it for a book on the beehive cells of the Hebrides, which I hope to get published later this year.)

|

| The view west from Beinn a' Bhoth to Loch Reasort and Scarp |

The cell had a spectacular view west to Loch Reasort and the Atlantic, with the island of Scarp on the far horizon. A more perfect place to spy on unwanted arrivals by sea would be hard to find. I regretted leaving my tent at Airigh an t-Sluic, as this would have been a memorable place to camp. But it was for the better, as the severe winds I experienced that night would have been much stronger at this elevation.

The sun relentlessly blazed down as I left the cell to spiral up to the summit. A joyful surprise startled me when I crested a small rise. On its far side was a large pond; in it a dozen deer lazily enjoying a cool soak. When they noticed me they jumped up in unison, causing sprays of water to erupt into the air. Then they elegantly sprinted away at breakneck speed. Within five seconds the only sign of their presence were ripples of water slowly spreading across the surface of the pond. By the time I got the camera out they had reached the ridge top above me.

|

| Look north from the summit of Beinn a' Bhoth |

I took some time to enjoy the 360-degree view from the summit of Beinn a’ Bhoth, then headed down its grassy eastern slopes. It was a 300-foot drop to the boggy floor of Gleann a’ Ghàraidh (they are all boggy), where I forded the Abhainn Gleann a’ Ghàraidh. As I ascended the hillside east of the stream a shout of joy burst forth—which scared a snoozing grouse out of the heather. At the shieling settlement known as Griosamul stood a compact triple beehive cluster, one of the cells 100% intact. It was the other cell I'd seen on the aerial photo, marked on the map as Both a’ Ghriosamul.

There were once three beehives clustered close together atop a mound at the center of the site, two of them interconnected. Only one of the three stands complete, and it is one of the best intact cells anywhere. After crawling inside I could see that the only large gaps in its dome were the smokehole at the top, and a small window to let the occupants keep an eye on what’s going on down in the glen. Having a window opening is unusual, the only other cells I know of with windows are St Ronan’s Cell and one of the beehives at Gearraidh Aineabhal. Inside the cell lay an old whisky bottle - unfortunately it was empty.

|

| Inside the cell - Both a' Ghriosamul |

|

| Looking north over the cell at Griosamul |

I am glad the users of this shieling site left one of the cells intact, for there was no mystery as to where the stones of the other cells had gone. At the base of the mound stood the ruin of a newer, oval shieling hut, obviously made from the pillaged stones of the other cells. And 100 feet to the north lay the foundation of another beehive almost completely plundered for its stone.

After leaving a note for the next visitor I crawled out of the cell, and then made a level crossing of the wide glen back to the shielings at Airigh an t-Sluic, where I’d stashed the tent and sleeping bag three hours earlier. As the sun started dipping west I pitched the tent by the meager remnants of a shieling hut. I fell asleep atop the sleeping bag in the hot, sun-baked tent, only to wake shivering at midnight as a storm blew through.

Lashing rain and howling winds came and went all night. In the morning I put off getting up as long as possible, hoping the rain would stop. But it didn’t. It was only after rolling up the wet tent, and strapping it to my pack, that the rain decided to stop. It was time to return to Morsgail, but only after making one more stop.

I headed to the northwest over a mist-shrouded ridge to find one of the old paths that lead north to Morsgail. These old, mostly abandoned paths are more interesting to follow than the muddy, quad-bike tracks that scar the moorland. Here and there these older routes cross substantial, and in some cases elegant, stone-slab bridges built in the early years of the estate. After crossing one of those bridges I came to a large, sunken, brown swath of moorland, 600 feet long and 200 wide, that marks the site of a vanished loch.

|

| What's left of Loch nan Learga |

Here I stopped to gaze skyward, hoping that a flaming interplanetary traveller would not plunge down on me. For it’s said a meteorite destroyed the loch that once lay here. In 1959 the missing loch, Loch nan Learga, collapsed in what is known as a peat slide, or bog burst. Its water draining into nearby Loch Mòr Shèlibridh. But what triggered it? It was possibly heavy rainfall, but at the Aird Uig radar base, twenty kilometres northwest of the loch, a giant “burning ball of hell” reportedly flew overhead. An expedition to the area discovered that the loch had drained. But there was no sign of any meteoritic debris.

|

| The vanished loch and the final Postman's Stone |

Fortunately, no meteorites plunged down on me as I carried on across the bog—talk about going out in a blaze of glory—oh, to think how the books would sell after that! Near the vanished loch a pillar-stone stands atop a large mound, visible for quite a distance. It is a significant stone, a guide-stone, the last of the Postman’s Stones that lead you across the bogs from Kinresort to Morsgail. From there it was an easy trek back to the Beinn na Gile beehives, and then on to the quiet road at Kinlochrog.